Tunnel Hazard Devlog: Rebuilding the Player State Machine

State Machines

State machines provide a very clear model for defining different behaviors based on the current state of a given element. In working on this game, I originally went with a very basic state implementation for the Player object which relied on a state enumeration. Enumerations and checks can be OK for very simple objects, but past a few states or where behavior starts to overlap it becomes very unwieldy. The player script was littered with state checks and a very long function which updated various animations on state change. This was confounded with a number of boolean flags which would interact only with certain states. This is an example of one of those messy check trees:

func set_state(new_state: PlayerState) -> void:

if new_state == state:

return

state = new_state

if state not in [PlayerState.WALK_LEFT, PlayerState.WALK_RIGHT]:

$RunningDust.emitting = false

match state:

PlayerState.LOCKED:

$PlayerSprite.stop()

$HatSprite.stop()

PlayerState.IDLE:

$PlayerSprite.play("idle")

$HatSprite.play("idle")

if has_cat:

$CatPackSprite.visible = true

$CatPackSprite.play("idle")

PlayerState.WALK_LEFT:

$RunningDust.process_material.gravity = Vector3(10, -5, 0)

$RunningDust.emitting = true

$PlayerSprite.flip_h = true

$HatSprite.flip_h = true

$PlayerSprite.play("walk")

$HatSprite.play("walk")

if has_cat:

$CatPackSprite.visible = true

$CatPackSprite.flip_h = true

$CatPackSprite.play("walk")

# most of this function has been omitted for brevity.

# It was 37 lines long as of v1.0, mostly one huge match tree

Other functions had a bunch of state exclusion checks such as this:

#example of state checks in various functions

elif state in [PlayerState.DEAD, PlayerState.DYING, PlayerState.LOCKED]:

return

With the pending addition of jumping, I reached the limit of tolerable complexity in this system and needed to transition to more robust implementation that didn’t feel one step removed from a bowl of spaghetti.

Enter the node-based state machine, where much of this functionality is removed from the player script altogether and delegated to state scripts via a StateMachine object.

@onready var _state_machine: StateMachine = $StateMachine

func _ready() -> void:

position = INITIAL_POSITION

_state_machine._transition_to("idle")

func _physics_process(delta: float) -> void:

_state_machine.process_input()

_state_machine.process_physics(delta)

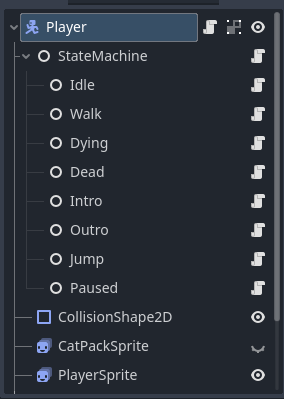

Each state is now a separate basic Node with an attached script:

The player simply passes calls down to the StateMachine, which relays them to the current state if it’s a state-specific functionality while directly handling tasks such as changing state. All the player object knows how to do is change itself as needed, such as showing or hiding various sprites, flipping sprites, and tracking its own stats. The states, each of which holds a reference to the player, initiate the other changes such as updating the player’s velocity or instructing the player to switch animations.

extends Node

class_name StateMachine

@export var default_state: State

var _states: Dictionary[String, Node] = {}

@onready var current_state: State = default_state

@export var player: Player

func _ready() -> void:

for child in get_children():

if child is State:

_states[child.name.to_lower()] = child

child.player = player

child.connect("request_transition", _transition_to)

_transition_to(default_state.name)

func _transition_to(target_state_name: String) -> void:

target_state_name = target_state_name.to_lower()

if target_state_name not in _states:

print("Invalid state name %s" % [target_state_name])

return

var new_state: State = _states.get(target_state_name)

if current_state == new_state or new_state == null:

return

current_state.exit()

current_state = new_state

current_state.enter()

# pass calls to held state

func process_physics(delta: float) -> void:

current_state.process_physics(delta)

func process_input() -> void:

current_state.process_input()

func take_hit() -> void:

current_state.take_hit()

func can_catch_cat() -> bool:

return current_state.allow_catch_cat

Consider for example the walk states. The original implementation used PlayerState.WALK_LEFT and PlayerState.WALK_RIGHT enum values, with a lot of duplicated code and checks for each. The new state setup uses one Walk state, which also controls the direction the player will face and move based on delegated input handling.

All States extend the base State class which provides some key variables and base functions.

@abstract

extends Node

class_name State

signal request_transition

@export var animation_name: String

@export var player: Player

@export var allows_hits: bool = false

@export var allow_catch_cat: bool = false

func enter() -> void: # on starting this state

if animation_name:

player.main_sprite.play(animation_name)

player.hat_sprite.play(animation_name)

player.catpack_sprite.play(animation_name)

func exit() -> void:

player.main_sprite.stop()

player.hat_sprite.stop()

player.catpack_sprite.stop()

@abstract

func process_input() -> void

func take_hit() -> void:

if allows_hits:

request_transition.emit("dying")

func process_physics(delta: float) -> void:

if not player.is_on_floor():

player.velocity += player.get_gravity() * delta

player.move_and_slide()

This is the entire Walk state script, which has some specific functionality for input handling and the physics update tick, but otherwise relies on defaults:

extends State

func enter() -> void:

super()

func exit() -> void:

super()

func process_input() -> void:

var walk_direction: float = Input.get_axis("move_left", "move_right")

if Input.is_action_pressed("jump"):

request_transition.emit("jump")

elif is_zero_approx(walk_direction):

request_transition.emit("idle")

func process_physics(delta: float) -> void:

var walk_direction: float = Input.get_axis("move_left", "move_right")

player.orient_to_left(walk_direction < 0)

player.velocity.x = walk_direction * player.WALK_SPEED

super.process_physics(delta)

States are also now responsible for triggering the player’s signals which are subscribed to by the game manager class to coordinate stage changes and intro/outro sequences. With this system, adding a new jump state occurs entirely within a separate Jump script and involves zero edits to the player script. It’s a much cleaner approach that prevents side-effects to existing functionality because the update no longer requires broad changes to a dozen different checks.

I’m sure there are better implementations out there and this is not perfect, so none of the above is proposed as the “correct way” to do things especially in far more complex scenarios. It’s definitely a pattern that I will be expanding on in future projects.